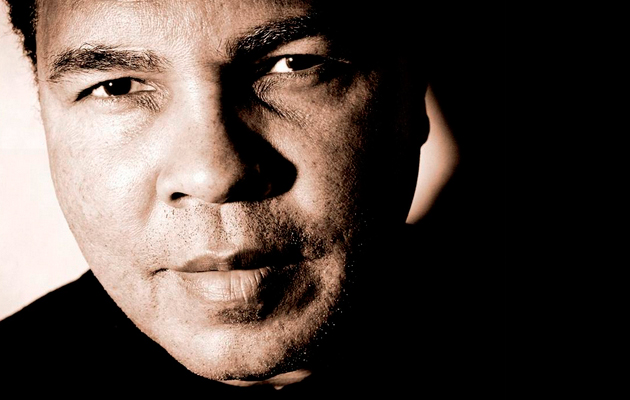

Legendary three-time heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali, who bragged that he was “the greatest” and then backed up the claim in the ring, died Friday in Phoenix, Arizona. He was 74.

Legendary three-time heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali, who bragged that he was “the greatest” and then backed up the claim in the ring, died Friday in Phoenix, Arizona. He was 74.

A family spokesman, Bob Gunnell, issued a statement saying that Ali died late Friday. “After a 32-year battle with Parkinson’s disease, Muhammad Ali has passed away at the age of 74. The three-time World Heavyweight Champion boxer died this evening,” Gunnell said.

The boxing great’s funeral will be Friday in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. There will be a funeral procession through the streets of the city and President Bill Clinton, Bryant Gumbel and Billy Crystal will be among those speaking at the inter-faith ceremony.

Ali, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s syndrome in 1984, the result of taking too many punches during his years in the ring, particularly at the end of his career, was hospitalized on June 2 in Phoenix for a respiratory ailment.

Ali’s gift of gab, fearless braggadocio, and outspoken politics made him a pop-culture icon in equal measure to his prodigious talents as a pugilist. Movies about his exploits won an Academy Award (the 1996 Oscar for best documentary for Leon Gast’s “When We Were Kings”) and were nominated twice more ( Will Smith and Jon Voight for actor and supporting actor in the Michael Mann-directed 2001 biopic “Ali”).

Born in Louisville in 1942 as Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., he began boxing at the age of 12, winning a number of amateur titles, culminating in an Olympic gold medal as a light heavyweight at the 1960 Games in Rome. He turned pro soon after that.

Early in his career, he battled societal norms as frequently as he did his opponents. In 1964, as the struggle for civil rights simmered, he knocked out heavy favorite Sonny Liston to win the heavyweight title for the first time, then told reporters that he was a member of the Nation of Islam and had changed his name to Muhammad Ali, a name many news outlets at the time were slow to recognize.

By 1967, he had successfully defended the title nine times, all but two by knockout. With the Vietnam War raging, he refused induction into the U.S. Army, on religious grounds, and was arrested and charged with draft evasion. When prodded further for his reasons for resisting, he said, “I am not going 10,000 miles to help murder, kill, and burn other people to simply help continue the domination of white slave-masters over dark people the world over.”

Though he remained free on appeal, he was stripped of his title and not allowed to box for more than three years. The conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court, unanimously, in 1971. (A 2013 film by Stephen Frears, “Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight,” which dramatized the court’s decision, debuted in Cannes, aired on HBO in the U.S., and earned an Emmy nomination.)

During his exile from the ring, Ali decided to try acting, starring in the 1969 Broadway musical “ Buck White “ at the George Abbott Theatre. He played a militant black lecturer, and got better reviews than the show, which closed after seven performances. “He sings with a pleasant slightly impersonal voice, acts without embarrassment and moves with innate dignity,” wrote New York Times reviewer Clive Barnes.

Ali also stayed in the public eye as a talk-show guest for the likes of Merv Griffin, David Frost and William F. Buckley (“Firing Line”).

Ali’s boxing career was defined by his matches against top opponents, particularly rivals Joe Frazier and George Foreman. His 1971 bout with Frazier to unify the heavyweight championship, his third after being reinstated, was called the Fight of the Century. Among those in attendance at Madison Square Garden were Miles Davis, Barbra Streisand, and Sammy Davis Jr. Burt Lancaster was the color commentator for the closed-circuit TV feed. Life Magazine hired Frank Sinatra as the photographer for Norman Mailer’s story.

Ali had exploded the era of humble sports heroes when he declared, “I am the greatest!” in the run-up to his title fight with Liston. He also was among the first athletes to trash-talk his opponents, and he called Frazier, who supported the war, an Uncle Tom. Frazier knocked down Ali in the 15th round, and won a unanimous decision.

Ali had to wait three years for another shot at the championship, this time against Foreman, who had beaten Frazier so badly in taking the title that few gave the 32-year-old challenger a chance against the 25-year-old champ. Ali called the fight, held in Kinshasa, Zaire, the Rumble in the Jungle. In documenting the bout 22 years later, Gast’s Oscar-winning “When We Were Kings” showed how an ebullient Ali had arrived on the scene a few days before the taciturn Foreman, and won over the nation’s citizens. An impromptu entourage of hundreds followed him around chanting, “Ali, bomaye!” (Ali, kill him!).

In perhaps an early kind of rap, Ali made a habit of rhyming his predictions, with his most famous coming ahead of the Liston fight, and playing off his talent as likely the fastest, most elusive heavyweight of all time: “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. Your hands can’t hit what your eyes can’t see.” (A 1963 spoken-word album released by Columbia Records, called “I Am the Greatest” featured the Olympic champ performing his poetry, backed my musical accompaniment.) For his battle with Foreman, an older Ali devised the strategy of “rope-a-dope,” laying back on the ropes that surround the ring and taunting Foreman to hit him. In the eighth round, after the much larger champion had punched himself to exhaustion, Ali sprang, and scored a knockout.

In 1977, Ali lent his name to a short-lived NBC animated series “I Am the Greatest!: The Adventures of Muhammad Ali.” Somewhat more memorably that year, he joined Sylvester Stallone — whose “Rocky” was to win best picture — to present the best supporting actress award to Beatrice Straight for her role in “Network.”

In the ring, a third, brutal fight against Frazier (the “Thrilla in Manilla”) as well as battles with Ken Norton subjected Ali to a great deal of punishment. And though he would become the first heavyweight to reclaim the title for a third time in 1978 at age 36, when he beat 25-year-old Leon Spinks in a rematch, the wear and tear of a career in boxing was apparent.

He retired, and stayed that way for two years, but ill-advisedly returned for two more bouts, with Larry Holmes and Trevor Burbick, both cringe-inducing losses.

Ali was, in many ways, a forerunner of the modern athlete. His brashness informed the likes of Joe Namath, and his black consciousness was echoed in the silent, solemn protests of track and field medalists John Carlos and Tommie Smith at the 1968 Olympics.

His ability to play to the media was legendary, and his relationship with Howard Cosell, contentious yet playful, furthered the careers of both men. Cosell was the first national broadcaster to refer to the champ by his Muslim name, and Ali’s outspokenness — another nickname he earned was the Louisville Lip — rescued a sport that had been dying, and hasn’t been as popular since he retired.

In 1996, 12 years after his Parkinson’s diagnosis, Ali, showing the effects of the disease, lit the torch to begin the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. In 2005, he was presented with the medal of freedom by President George W. Bush.

Ali is survived by his fourth wife, Yolanda “Lonnie” Williams, two sons, and seven daughters, including Laila Ali, a boxer who retired, undefeated, in 2007.

© 2016 Variety Media, LLC, a subsidiary of Penske Business Media; Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC